Milkweed for more than monarchs: 10 neat things

Milkweed isn’t just for monarch butterflies. Native milkweed (Asclepias) is one of the most fascinating and ecologically valuable plant groups you can grow. With dramatic flowers, a defence system straight out of a sci-fi movie, and a history that includes both ancient medicine and World War II life jackets, milkweed has more layers than you’d ever guess. Whether you’re growing it for pollinators, restoration, or just plain curiosity, here are 10 neat things about milkweed.

1. Monarchs depend on it for a toxic twist.

Monarch butterflies lay their eggs only on milkweed. That’s because milkweed leaves contain cardenolides—natural toxins that make the caterpillars and adult butterflies taste awful to predators. Their striking yellow-and-black caterpillar stripes are a loud warning: “Don’t eat me.” It’s a remarkable evolutionary partnership that keeps monarchs safe—provided there’s enough native milkweed to go around.

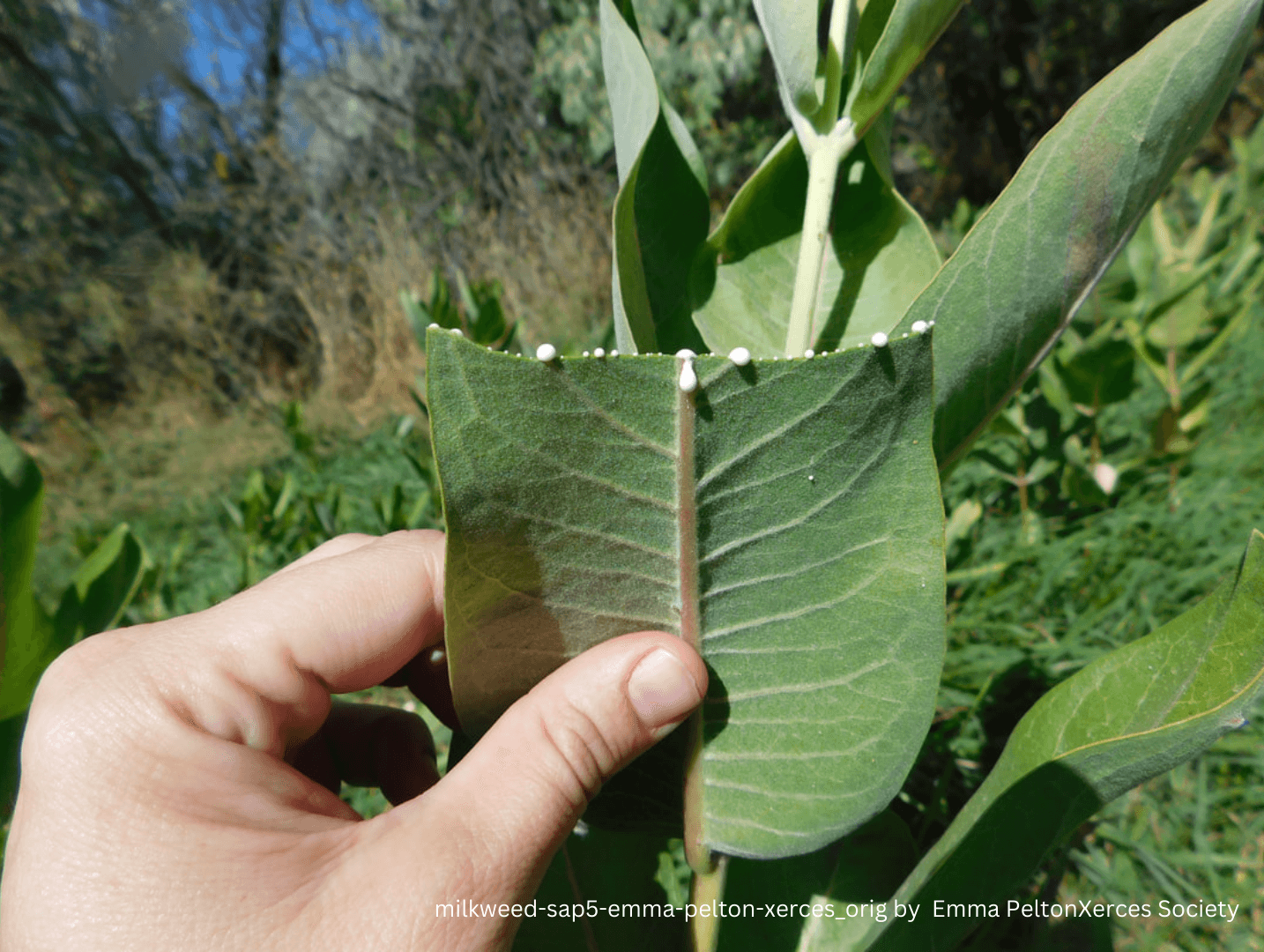

2. That white sap is more than just sticky.

Snap a milkweed stem and you’ll see white, latex-rich sap ooze out. This goo isn’t just messy—it’s a chemical defence packed with bitter compounds that deter herbivores and can glue the mouthparts of small insects shut. That latex is the reason many animals give milkweed a wide berth, even though the plant is loaded with nectar and pollen.

3. The flowers trap insects for a good reason.

Milkweed flowers look charming, but they’re actually insect traps in disguise. Their complex structure includes tiny slits between the flower’s hoods and horns, where insects like bees and butterflies can accidentally wedge their legs. In the struggle to escape, they either pick up or deposit a pollen sac. It’s risky, but rewarding—nature’s version of an escape room.

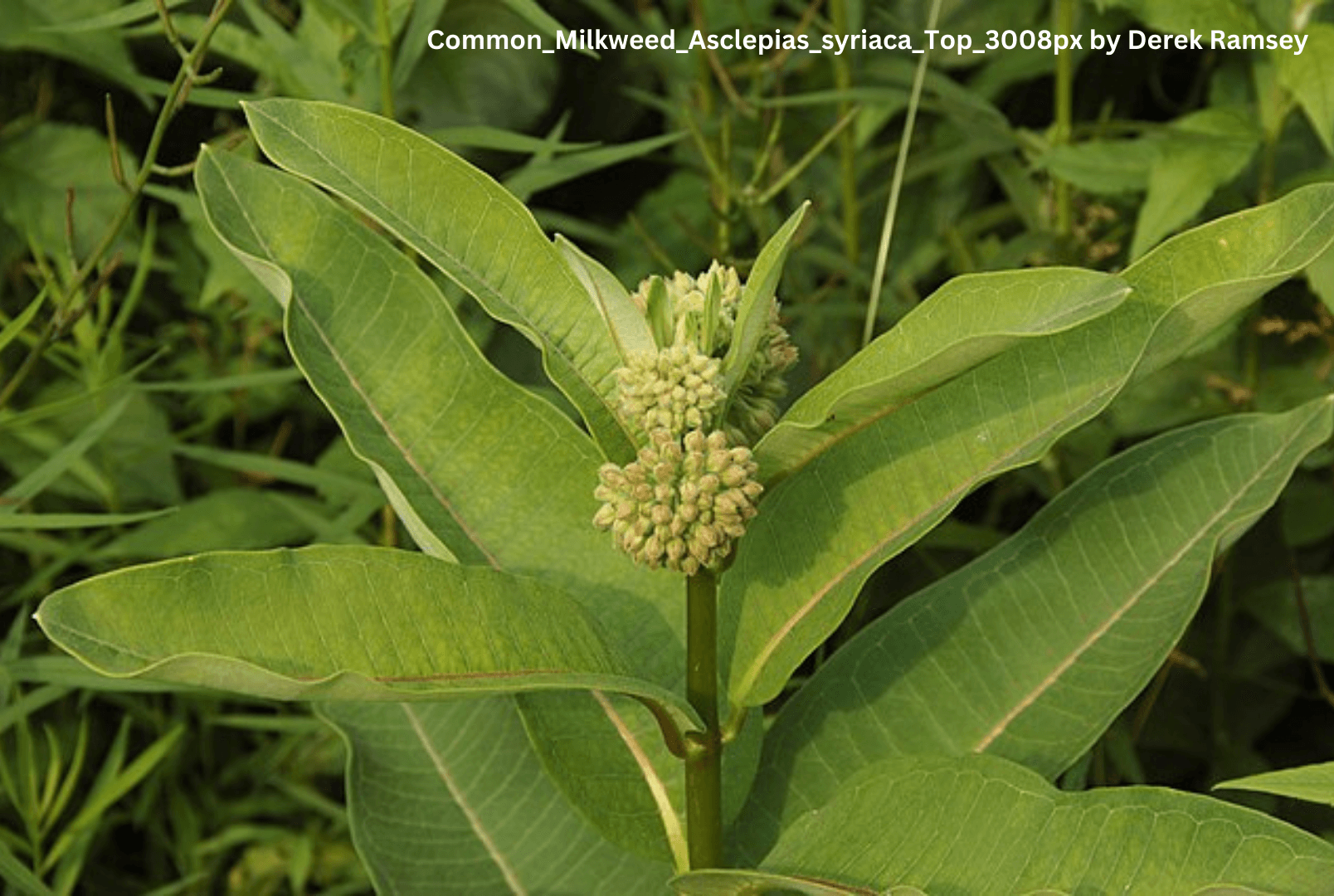

4. It’s named after a Greek god of healing.

Asclepias gets its name from Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine. Carl Linnaeus chose the name because some species, like common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), were used by indigenous North Americans to treat lung and skin ailments. But be warned: while some parts of the plant were once medicinal, most species contain powerful cardiac glycosides and should not be ingested.

5. There are more kinds than you’d expect.

More than 70 species of Asclepias grow in North America, each adapted to different habitats—from dry prairie to wetland. Canadian native milkweeds include Asclepias syriaca, A. incarnata, A. tuberosa, A. speciosa, and several others. Growing native species supports local pollinators and avoids problems caused by non-native milkweeds like A. curassavica, which can interfere with monarch migration.

6. Trouble germinating? They need cold.

If your milkweed seeds didn’t sprout, it’s likely they missed winter. Most native species require cold, moist stratification to break dormancy. You can simulate this by refrigerating seeds in a damp paper towel for 4 to 8 weeks. Or just sow them outdoors in autumn and let nature handle it.

7. Milkweed was wartime survival gear.

During WWII, children across Canada were enlisted to collect milkweed pods. The fluffy fibres inside, called floss, replaced kapokfibre (mostly harvested from Asia) in life jackets for naval personnel. Lightweight, water-resistant and buoyant, milkweed floss helped keep sailors afloat. It’s one of the most surprising historical uses for a native plant.

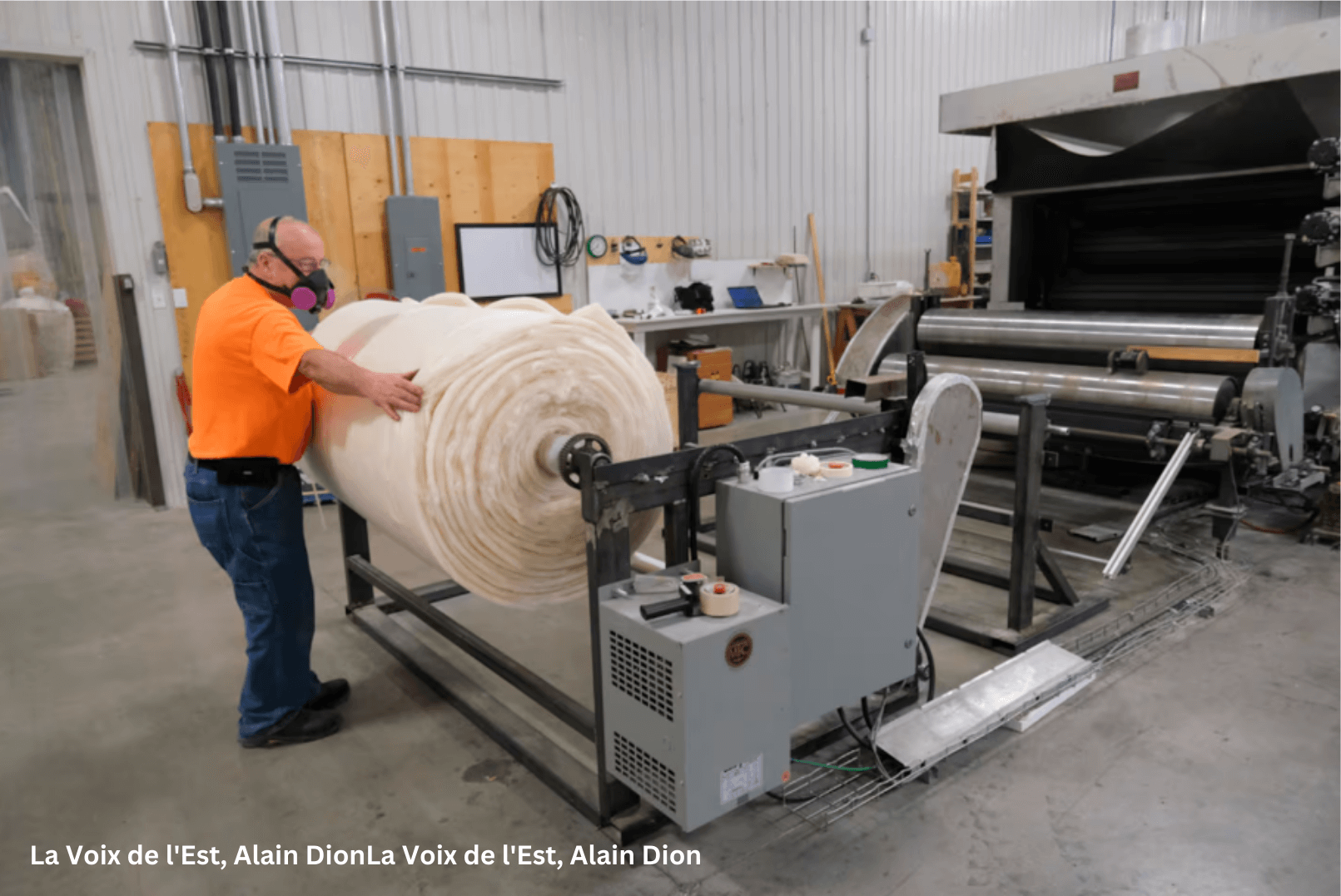

8. It’s being turned into eco-insulation.

In Quebec, a company called Eko-Terre is turning milkweed floss into Vegeto, an eco-friendly insulation used in outerwear. This sustainable material combines milkweed fibres with biodegradable plastic to create lightweight, warm, and water-resistant textiles—all harvested after monarchs have completed their lifecycle.

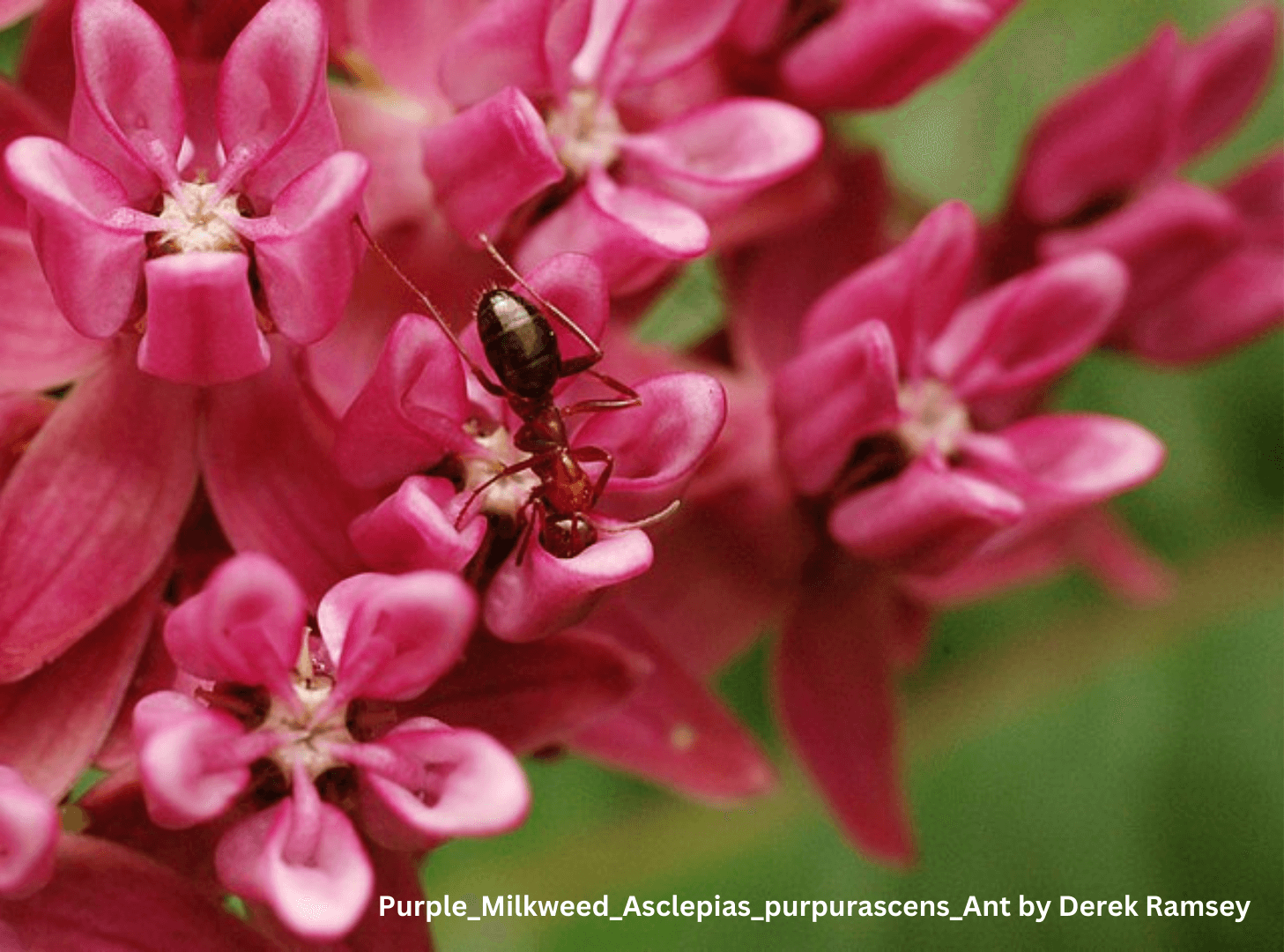

9. Ants act as tiny bodyguards.

Milkweed plants attract ants with sugary nectar from tiny glands on their stems and leaves (not just in the flowers). In return, the ants attack plant-eating insects like aphids and beetle larvae. But even this beneficial relationship has a dark side: sometimes monarch caterpillars fall victim to these aggressive protectors.

10. It’s a native plant hero for restoration.

Milkweed is now a cornerstone of habitat restoration. Its deep taproots improve soil structure, prevent erosion, and survive drought, fire, and mowing. Provinces are using it in roadside seed mixes to create pollinator corridors, reconnecting fragmented ecosystems and supporting biodiversity. If you want to grow for pollinators, this is your plant.