Seed-starting science: 10 neat things

Starting plants from seed is both an art and a science. While many gardeners focus on soil, water, and light, the hidden biological mechanisms that drive germination are even more fascinating. From seeds that won’t sprout without a cold snap to those that communicate using faint light signals, nature has fine-tuned its reproductive strategies for survival. Whether you’re a seasoned gardener or a curious beginner, these ten science-backed seed-starting insights will change how you think about growing plants from scratch.

1. Scarification science.

Some seeds, like sweet peas, morning glories, and nasturtiums, have hard outer coatings that prevent water absorption. In nature, these coatings wear down over time or after passing through an animal’s digestive system. You can mimic this process by thinning the seed coat with a file or soaking seeds in warm water to encourage germination. If you’re a seed-starting pro, you probably already knew this one, but read on—these Neat Things get more complex as the numbers get higher.

2. The role of phytochrome.

Seeds sense light using a pigment called phytochrome, which helps determine when conditions are right for germination. Some seeds, such as lettuce, petunias, and snapdragons, need light to sprout, while others, like beans, marigolds, and zinnias, require darkness. Burying or exposing seeds incorrectly can significantly impact success rates, so always check seed packet instructions.

3. Thermodormancy explained.

Some seeds won’t sprout if it’s too warm. Lettuce, poppies, and delphiniums experience thermodormancy, meaning they may refuse to germinate if soil temperatures exceed a certain threshold (often around 25Celsius). If you struggle with these seeds in midsummer, try pre-sprouting them in a cool, damp paper towel before planting.

4. Hydrogen peroxide hack.

A hydrogen peroxide soak can speed up germination for some stubborn seeds by breaking down inhibitors on the seed coat and increasing oxygen availability. Soaking seeds in a 3-percent hydrogen peroxide solution (the strength at which it is usually sold) for about 30 minutes, followed by a rinse, can help slow-sprouting plants like parsley, carrots, and larkspur germinate more quickly.

5. Fungal friends and foes.

While damping-off fungus is the enemy of seedlings, certain beneficial fungi, such as mycorrhizae, help seedlings establish strong root systems. Some commercial seed-starting mixes now include beneficial fungi to help seedlings absorb nutrients more effectively, leading to healthier, more resilient plants.

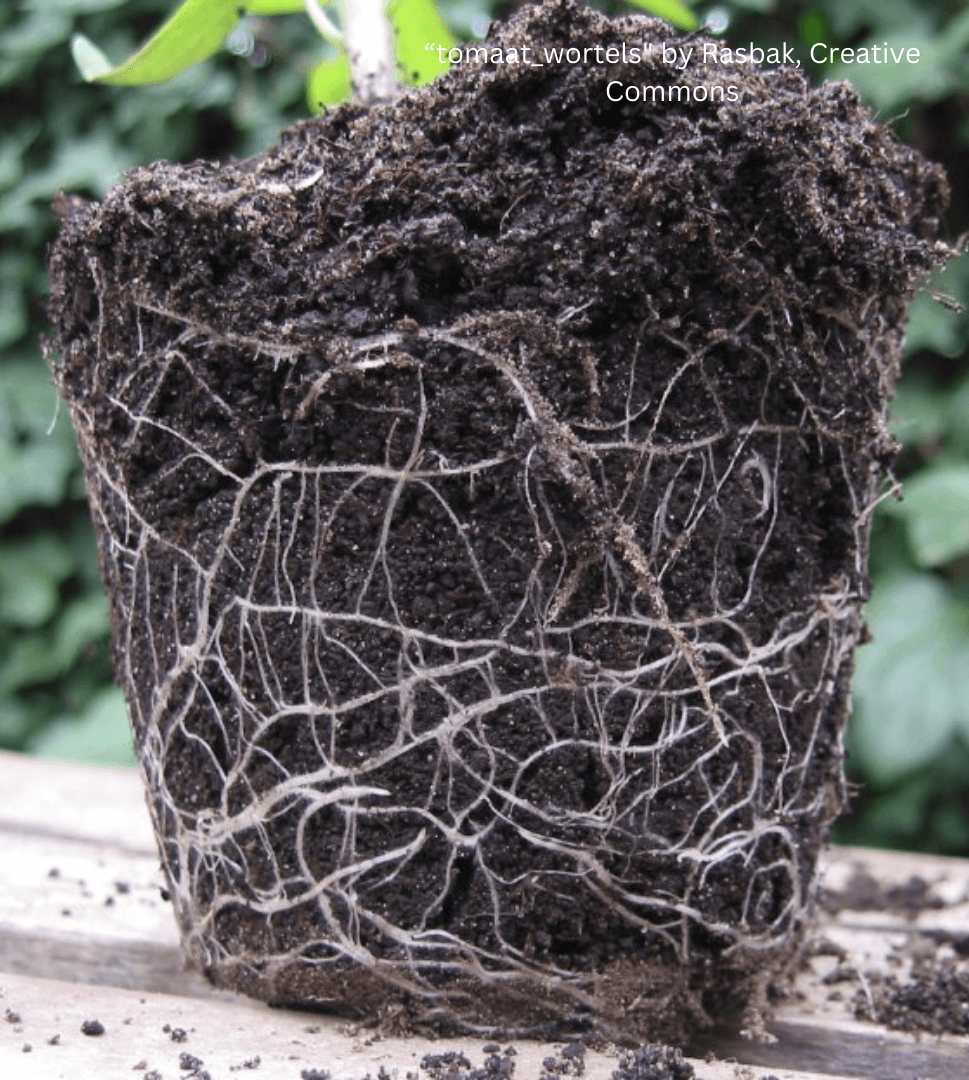

6. Air pruning for strong roots.

Traditional plastic seed trays can cause root circling, where roots spiral around the container’s edges. Air pruning, which happens in mesh-bottom trays, fabric pots, or soil blocks, naturally stops roots from circling and encourages a more fibrous, efficient root system. This technique is widely used in commercial nurseries for trees, vegetables, and flowers.

7. Biophotons in seedling development.

Plants emit weak light signals called biophotons, which may help regulate growth and germination. Some researchers theorize that seeds and seedlings use these signals to communicate stress levels or environmental conditions. While the practical applications of this research are still developing, it hints at a fascinating level of plant communication we don’t yet fully understand.

8. Magnetic and electrical stimulation for seed vigour.

Exposing seeds to a weak magnetic field has been shown to speed up germination and improve seedling growth, likely due to increased enzyme activity and better water uptake. Similarly, weak electric fields can enhance root development and increase stress resistance. Some commercial greenhouses are exploring these techniques to improve germination rates for crops and flowers. While it’s not a common gardening method yet, some curious home gardeners are experimenting with magnetized water to see if it improves results.

9. The aleurone layer’s hidden job.

Grains like corn and wheat have a special layer of cells called the aleurone, which produces enzymes that break down stored starch into sugars during germination. Without this process, the embryo wouldn’t have the energy to grow. Though this mechanism is most studied in grains, it plays a role in many other large-seeded plants as well, including lilies and sunflowers.

10. Why some seeds take years to sprout.

Certain perennials, shrubs, and trees have built-in survival mechanisms that delay germination for years, even decades. Seeds like prairie violet, wild columbine, and some milkweeds require long periods of cold (stratification) to break dormancy. Others, like lotus and some orchids, can remain viable for centuries if kept dry. Some ancient date palm seeds have been successfully sprouted after lying dormant for over 2,000 years!