10 Neat Things About Snow

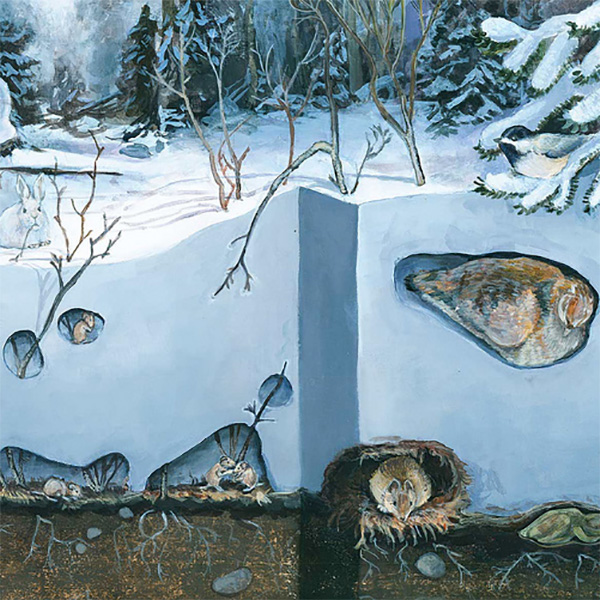

1. The pukak.

Under the winter’s collection of fallen snow, there is a secret world where small animals and insects spend the long, cold months dozing and foraging for food. This is the pukak layer, where it is always around zero degrees. Here, the heat of the earth has risen to the surface to melt and crystallize the snow, leaving gaps behind that can be turned into underground highways for the denizens of the pukak. Voles and mice and beetles use this highway, building air vents every so often to allow carbon dioxide to escape. This also signals their presence to predators that lurk near the vents waiting for dinner.

2. The silence of a winter’s eve.

Poets often refer to the silence surrounding snow including Robert Frost in his poem, “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening”:

The only other sound’s the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.

Fact is, though, snow, especially freshly fallen snow, has the power to absorb sound.

3. Squeak, squawk, creak.

If the temperature of snow is warmer than -10 Celsius, it will not squeak when you walk on it. This is because the pressure of your footstep partially melts the snow under it, allowing water to flow under your footfall. When it is colder than -10, the pressure from your weight crushes the ice crystals beneath your boot making that squeaking, or creaking, sound.

4. When snow falls as a ball.

This is known as a graupel or a snow grain or, most commonly, as sleet. Rime ice, that white stuff that coats tree limbs, is balls of white ice that form when fog droplets freeze at -2 to -8 Celsius. Hard rime is hard to shake off surfaces. Soft rime is feathery or spiky.

5. Snowflakes.

Snowflakes are really condensed water vapour which freezes directly into ice crystals. The simplest snowflake is a hexagonal prism, with a top and a bottom (basal facets) and six sides (prism facets). Snowflakes also form as hexagonal lattice crystals. As the snow crystal moves through the air, it tends to collide with objects, which causes a bump to form, usually at the corners first. These bumps then pick up new water molecules causing the bump to “grow” into branches. The branches pick up bumps and grow into side branches and so on. The final shape and how the branches form depends on temperature and humidity.

6. Are snowflakes all unique?

Each snowflake can contain one quintillion water molecules—that’s one million times one million times one million. What this adds up to is possibilities of formation that number more than twice the number of atoms in the universe. Sooo, mathematically speaking, probably all snowflakes are unique.

7. Snow falling on wings.

Ice on aircraft wings is dangerous because it disrupts air flow, decreasing lift and increasing drag. But aircraft can actually trigger snow, according to Science magazine. “When aircraft punch holes in low clouds, they are triggering extra snowfall,” an article claims. Propellers cool air up to 30 degrees which can cause ice crystals to form. Wings on high-speed jets can cool the air above the wings by 20 degrees, producing a stream of ice crystals behind the wings.

8. Canada’s biggest snow dump.

Mount Fidelity on the west side of Glacier National Park receives the most snow in Canada. It snows about 144 out of 365 days every year, depositing 48 feet of snow. Seven of the 10 snowiest places in Canada are in British Columbia. The other three are: #7 Nain, Newfoundland; #9 Cap Seize, Quebec; and #10 Churchill Falls, Newfoundland.

9. How heavy is snow?

The light fluffy stuff weighs in about five to seven pounds per cubic foot. A cubic foot of snow contains about 2.83 litres of water or five-eighths to three-quarters of a gallon. The ratio of snow to water is about 12 to one.

10. Snow blindness and wounded trees.

Snow is a wonderful partner for the sun when it comes to reflecting heat and ultraviolet rays. Snow can throw back more than 90 percent of the radiation and deflect it to your eye where it can cause photokeratitis, a painful condition that results in inflammation of the cornea. Fortunately, healing is rapid – 24 to 72 hours in a darkened room. Sun reflected on it can scald the bark of thin barked and young trees, by heating and reactivating tree cells which then refreeze when the sun is gone, causing the bark to split.

© 2023 Pegasus Publications Inc. https://www.localgardener.ca/